Anxiety

Anxiety is a feeling of fear or worry when we think that something may go wrong. Most people experience it when rushing to catch a train or before exams or interviews. We also experience it when meeting people for the first time because we worry about what the other person may think about us. We feel anxiety in our mind and body – our heart rate goes up and we may feel sweaty, and we find it hard to concentrate or listen to others. Sometimes, anxiety drives us to do things that we need to do. We look at its positive side and accept it as a part of life.

For some people, anxiety is either too frequent or too intense; it arises for no reason or an imaginary reason, and it is hard to be rid of. It may interfere with day-to-day life, for example, making it hard to leave the house, to start a new activity or meet other people. It may also interfere with attention and learning and may make them fidgety, irritable and upset.

Anxiety or fears are common in children; they are commoner in children with autism (affecting about 40%). Anxiety in children shows itself somewhat differently than in adults:

- Most anxious children have behaviour difficulties: anger, agitation, irritation, poor sleep or eating, reduced engagement with others, increased fixations on some objects or activities, and withdrawal from others.

- In children with autism, episodes of anxiety are longer lasting and more intense.

- Mostly, children’s anxieties are about changes in routines or situations, going to a new place or meeting new people.

- Some sensations, such as noise or light, can also provoke anxiety.

Types of anxiety problems:

Social anxiety, provoked when one has to meet another person or people, is the commonest form of anxiety in autism (29%); general anxiety about minor things, such as a fear of dogs, crossing the road or shifting from one activity to another, is also common (13%). In addition, some children have panic disorder (10%), and others have some specific fears, for example, agoraphobia – when the person feels trapped and fearful in a situation as in open spaces, shopping malls, train carriages, and wants to escape.

In some children with autism, anxiety gets worse with age. Adolescents with high functioning or milder forms of ASD may first come to notice of teachers or parents because of their fears and anxiety.

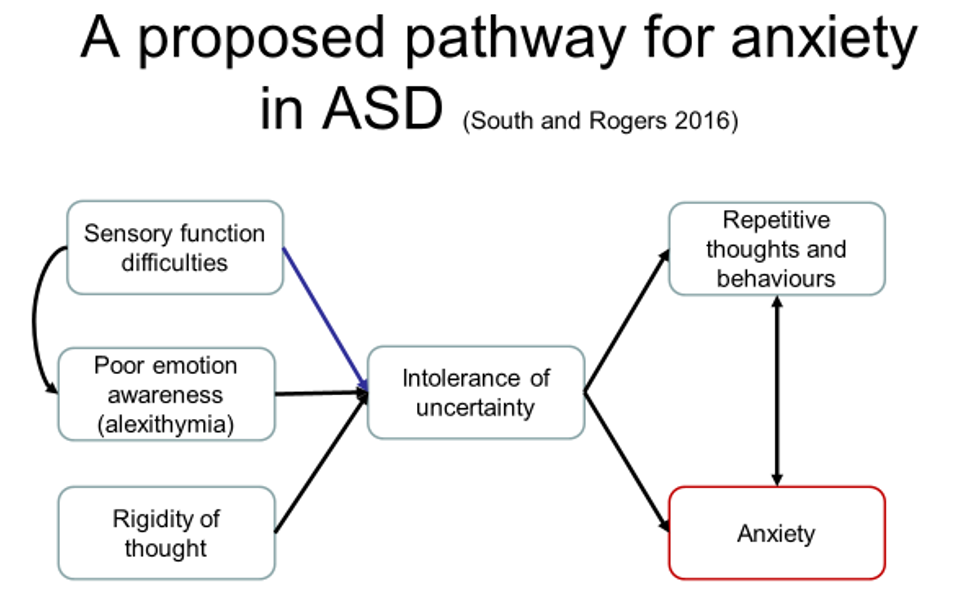

What causes anxiety in autism – Five factors that contribute to anxiety in autism:

-

Cognitive rigidity: a difficulty in shifting from an idea

- Lack of flexibility makes it hard to deal with new situations and makes a person intolerant of any unpredictable situations.

- Being rigid in thinking prevents the development of flexible strategies for dealing with stress.

- Anxiety increases rigidity, which in turn makes the person more anxious.

-

Sensory processing difficulties

Sensory processing helps us pick out the most relevant information and make sense of the whole situation when only some of the information is available, such as guessing the object when we can only see a part of it or filling in missing words in a sentence. This failure of making sense of the situation becomes a source of uncertainty and ongoing anxiety.

-

Difficulty in feeling, recognising, and expressing emotions (alexithymia)

We all have feelings, often provoked by a thought or memory, or seeing or hearing something. When we become aware of our feelings and emotions – being worried, angry, happy, rushed, or just bored then we do something to manage our feelings – by thinking this will pass, it is not a big deal, or we can sort it out later – or we act on our feelings – talk to someone or do something. This is how we maintain our mental balance. In autism, the feelings are often confused and chaotic, making it hard for people with autism to express or manage or act on their feelings. This creates a few problems for the person: a. they may become anxious or fearful of not knowing what is going on, b. it becomes hard for them to take the right action, c. their actions or behaviour are not helpful for them and may cause further problems, and d. they may suppress or bottle up their feelings leading to a build-up which explodes when it becomes too much.

-

Intolerance of uncertainty:

Uncertainty is not knowing about a situation or a person or an object:

- What is going to happen next?

- What will happen because of what I have done?

- When would this end?

- Should I do it or not?

While uncertainty is hard for everyone, it is particularly upsetting and distressing for people with autism. To avoid being upset, they might try to avoid the situation or work too hard to prepare for it, like gathering too much information or endlessly seeking assurance, repeatedly asking questions or ruminating, reading up or preparing for something that is relatively rather a minor issue. it may also make them highly anxious particularly if they have difficulty in managing their emotions and feelings. It may affect their thinking, make them more hostile, or cause physical symptoms such as excessive sweating, feeling hot or shaky or increased heart rate.

-

Not knowing how to relax and be calm

We all become stressed and anxious – that is life! However, to carry on, we need some downtime – some time to relax and wind down. We have our preferred way of doing it that we have learnt over some time, and it works for us; some people are better at relaxing and recharging, and they seem to be better able to cope with the stresses and demands of life. It is hard for people with autism to know when to relax and how to relax. But, if they are given a structure to recognise their stress and are helped to practice some relaxing methods, they too can learn it.

Triggers for anxiety

Most people become anxious when facing uncertainty. Even for children who become anxious easily, some situations act as triggers or starting points for anxiety:

- Change of routine

- Confusion and worries about social and communication situations

- If they are prevented from doing preferred repetitive behaviour

- Exposure to some specific sensations or overstimulation

- Exposure to situations that provoke fear

- If too many demands/expectations are made of them.

Assessing anxiety

- Functional assessment ( it may help to keep a diary to monitor if an intervention works or not or to understand what provokes or triggers anxiety):

- Make a note of the frequency, duration and intensity of anxiety episodes

- Make a note of antecedents (what happened before anxiety was provoked) and consequences (what happened after the person became anxious): for recognising triggers and maintaining or calming factors – factors that make anxiety last longer, such as, getting attention from others.

- Measure (these are used for clinical evaluation and research studies of anxiety):

- The Anxiety Scale for Children- ASD (ASC-ASD©) is a 24 item self-report anxiety questionnaire, with four sub-scales: Separation Anxiety(SA), Uncertainty (U), Performance Anxiety (PA) and Anxious Arousal(AA), for use with young people aged between 8-16 years with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). There are no norms yet but recommended clinical cut-off is 24. It is free to download and is available in multiple languages. https://research.ncl.ac.uk/neurodisability/leafletsandmeasures/anxietyscaleforchildren-asd/

But, not everything is anxiety!

- Sometimes demand avoidance is just demand avoidance

- Sometimes challenging behaviour has other reasons

Seven ways of helping an anxious child

-

Preventing anxiety – prevention is the best approach

- Diet, sleep, and exercise

- Reduce stimulating food from the diet.

- Lack of sleep worsens emotional regulation and anxiety. Make a calm sleeping routine to follow. Look at ‘Helping children sleep better’ to find out more.

- Regular physical exercise, 20-30 minutes at a time, 2 or 3 times a day, will help the child remain calm.

- Model non-anxious behaviour. Increase a sense of calm. Reduce clutter.

- ALL CHILDREN NEED DOWNTIME! Give opportunities for time out – and make sure that the child is confident to use them (for example, time out card)

- Try to use routines and consider using the following methods:

- visually communicate – visual timetables,

- Now and Next cards (for example, a picture of the current activity and a picture of the next activity)

- ‘bridging’ activities to fill the gap between the changes

- advance warning (whether it needs to be given well in advance of any change or a new activity or immediately before (long or short) depends on the child) and the situation.

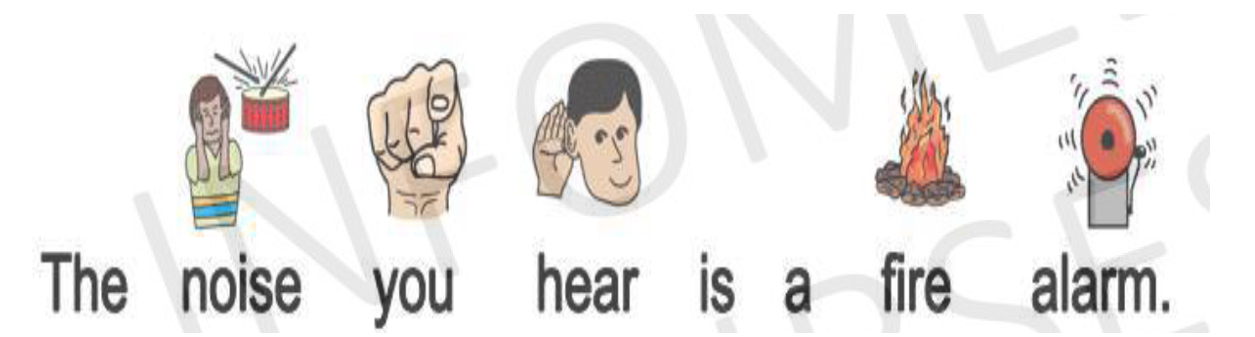

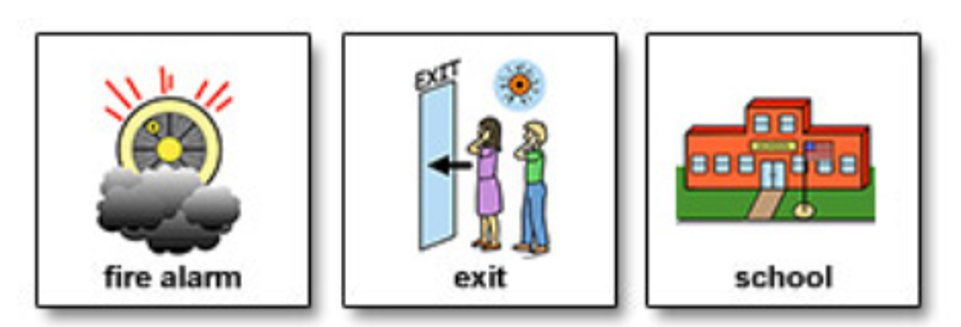

For example, there can be two types of warning about a fire alarm:

and:

- Yes, you need to push for new things, but do it slowly and gently.

- ‘Read’ the child’s behaviour – be aware of the impact of adult behaviour on the child (for example, perception of being shouted at/told off, criticised, feeling pressured, getting into battles). Then, have regular one-to-one time with the child.

- Praise – public vs private – be aware that being the focus of attention is uncomfortable for some children.

- Be alert for any teasing and bullying happening at the school or neighbourhood.

- Provide help in understanding instructions and communicating expression of the need for support – use signs or images if required.

-

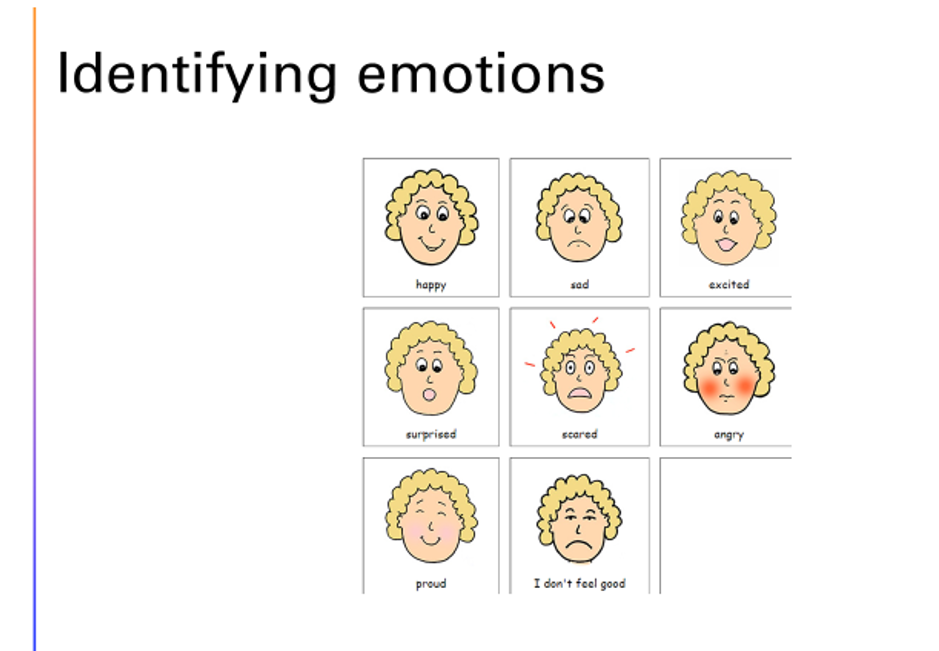

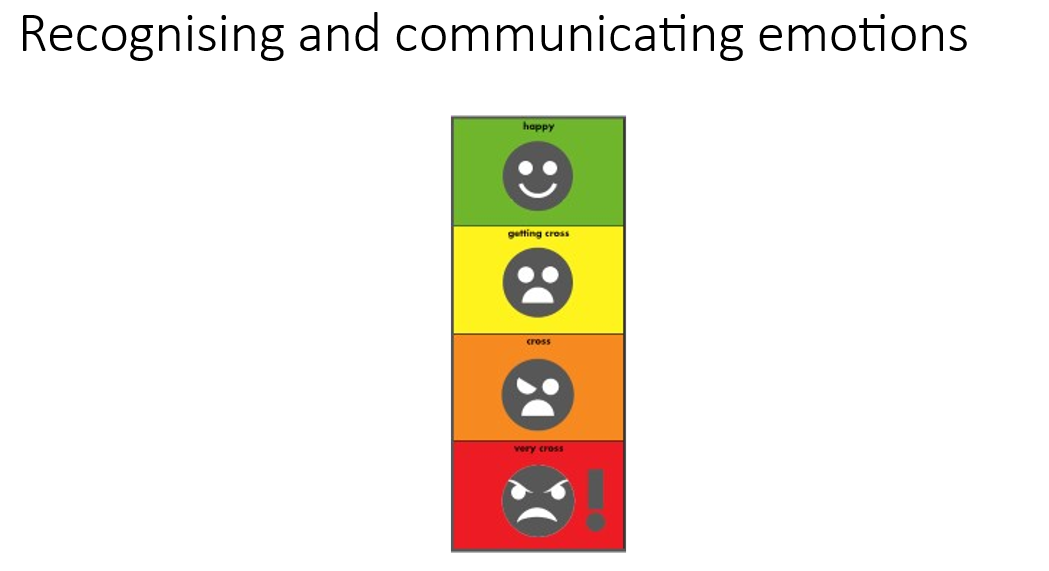

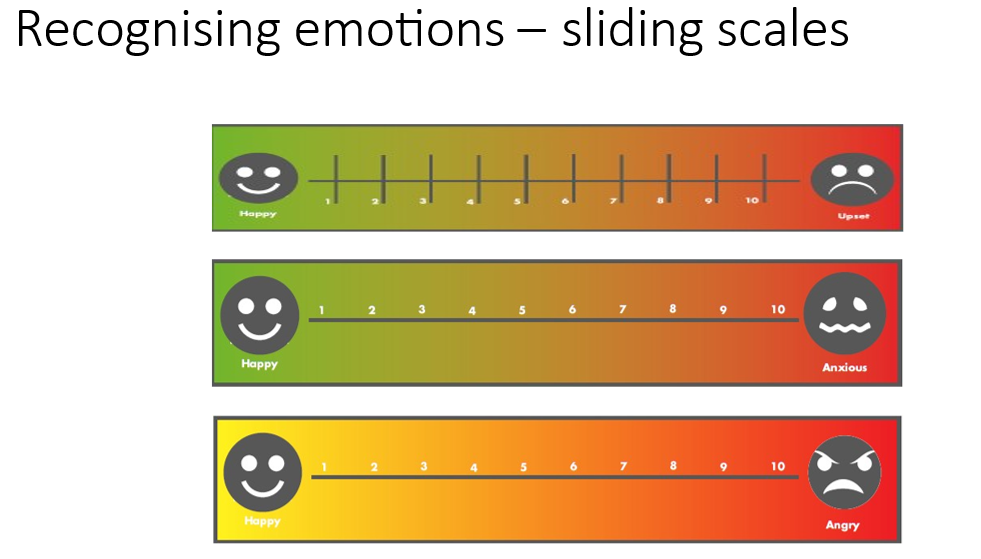

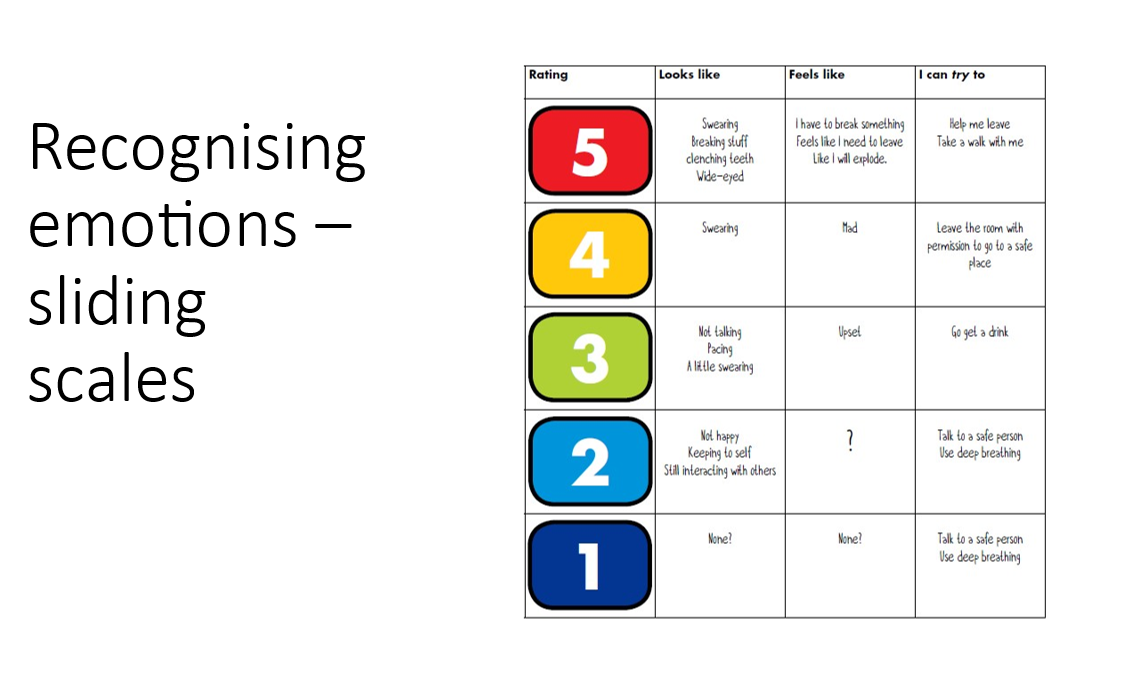

Help the child get better at recognising and communicating emotions

- Help the child learn to identify and express emotions

- Help them learn words or images to express emotions

- Make it easier for them to share their emotions by clarifying who they can share with, when and how.

- Help them learn what triggers their emotions

- Help them understand how emotions affect them.

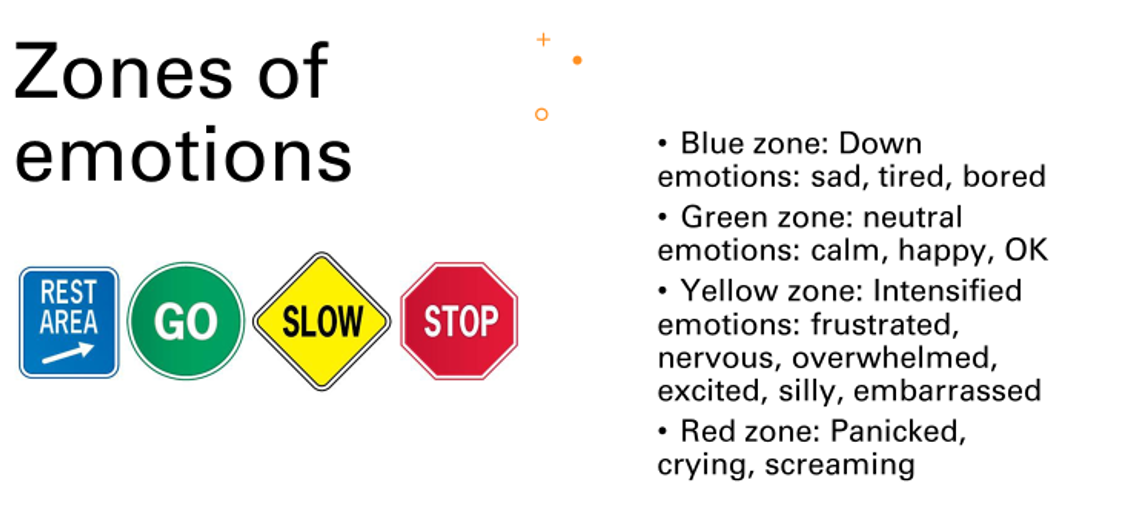

The colourful ‘Zones of regulation’ can also help a child label the intensity of how distressed, anxious, or upset they are.

Once they have used rating and labelling, they can communicate their emotions to others and learn how to manage them. Recognising and labelling is the first step in managing emotions.

Look at ‘Helping children’s emotional regulation’ to find out more.

3. Giving the right sensory experiences

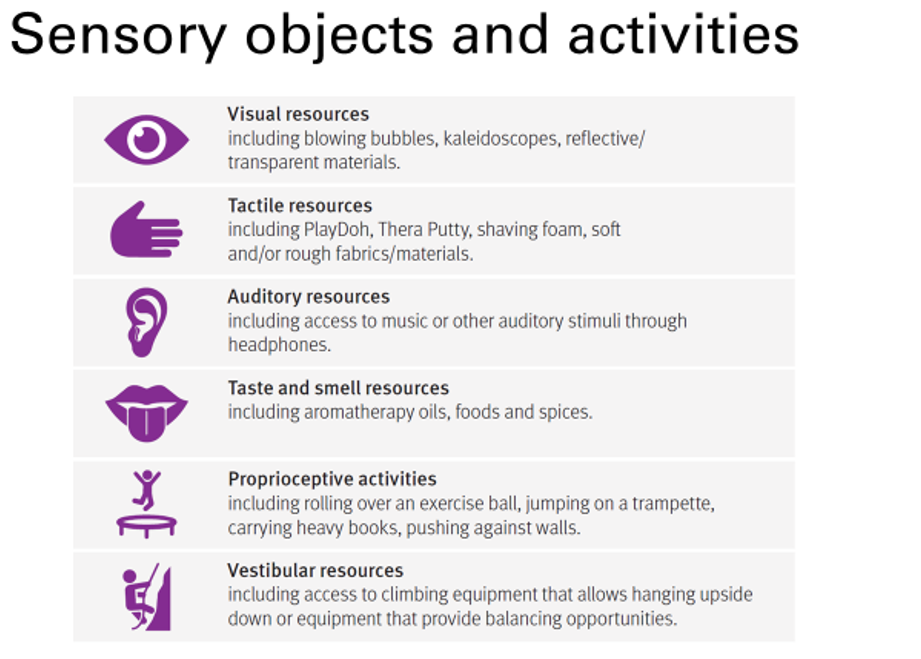

Many children with autism, who are hypersensitive – are distressed by light, noise or other sensations – benefit from reducing sensory input by using simple methods such as dark glasses or headphones. In contrast, others who have decreased sensitivities and seek sensations can benefit from giving them opportunities to do fun activities that involve visual, touch, sound or movement sensations.

Look at ‘Helping Children with Sensory Processing Difficulties’ to make the right programme for the child.

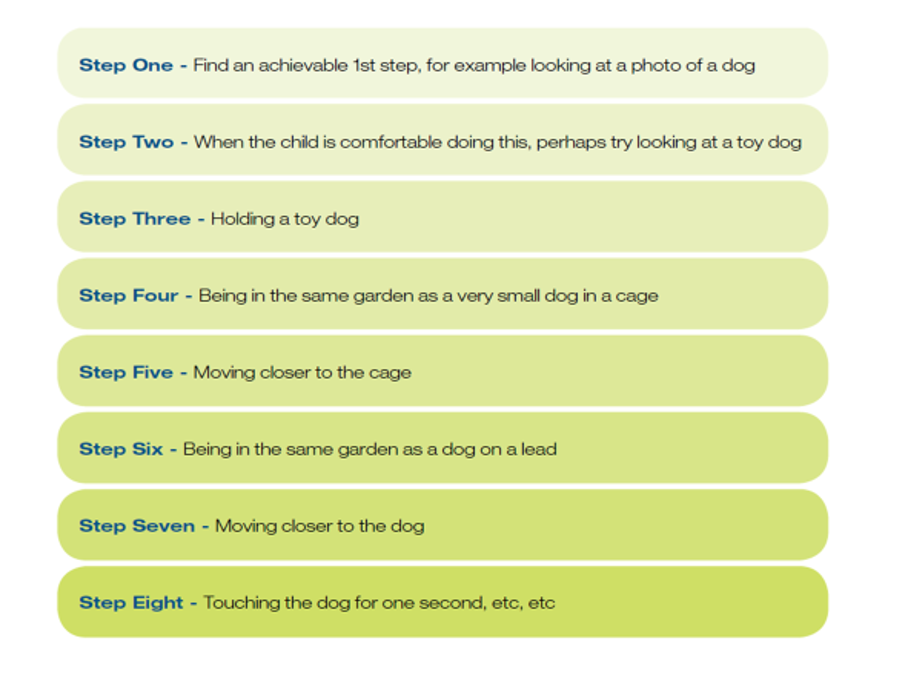

4. Supported gradual exposure to a feared situation

A step-by-step plan to gradually expose the child to a feared situation can help overcome a specific fear. The successful completion of each step is praised, and the next step is built on the previous one. For example, a plan to reduce the fear of dogs may look like this:

-

Getting better at dealing with uncertain situations

A vicious cycle of negative thoughts (“something wrong with me”, “It is going to get worse”) creates a sense of fear, and physical feelings (feeling shaky and sweaty). Breaking this vicious cycle is helped by using a mindful approach as the one described below:

- Say STOP in your mind, or even out loud if that helps

- Take five deep breaths: in through the nose and out from your mouth. Focus on your breath – feel the breath as it goes in and out.

- Pull back: tell yourself: “This is just anxiety; I don’t have to act on it just now; it will pass”.

- Ask for help, talk to patents, teacher, or a trusted friend,

- Shift your focus: use the practised activity such as reading, listening to music, using a sensory ball.

-

Getting better at dealing with a new demand or situation by preparing and by practising in a supportive environment

- Use visual aids and social stories to explain new situations and to support understanding of emotions.

-

Help the child learn to relax and be calm

Some useful strategies are:

- Physical exercise

- Belly Breathing

- Counting

- Thinking of pleasant situations (i.e. their favourite train)

- Gentle physical touch (hugs, squashing ball)

- Repetitive behaviours

Practice some simple activities such as lying down to the count of 10 or breathing deeply ten times, squeezing a squeezy ball, listening to music, looking at their favourite picture book or using a sensory activity.

Don’t wait for the child to get stressed before practising these activities, rather make them part of some of the routines you do with your child every day. Give the activity a one or two-word name, such as ‘airtime’, ‘sleeping lion’ or ‘squeezy ball’, and make a symbol for the activity. First, show the child that symbol, then say its name and then do the relaxing activity—model, prompt, and reward. Once the child has practised a particular relaxing activity quite a few times, you’ll show the child the symbol or say its name whenever the child is stressed or upset, and the child may then be able to relax when they need to relax. Practice a few of these activities regularly, and then you will be able to choose the right one at the right time. If you haven’t practised it before, you won’t be able to use it when you need to.

Working with the school

Children often become anxious in school, and it adversely affects their learning and behaviour. Work with the school to apply the above tips. Maintain good communication. Watch out for any bullying of the child at the school.

- Psychologist: for assessing the child and using adapted CBT

- Child psychiatrist: some children may need medication. All medication has side effects. It should only be used when all the above have been tried and with extreme caution.

Sources/references

An Evidence-Based Guide to Anxiety in Autism. Gaigg SB, Crawford J, Cottell H (2018). https://www.city.ac.uk/news/2019/april/new-guide-help-manage-anxiety-autism

Children and young people with anxiety: a guide for parents and carers. www.anxietyuk.org.uk

Dr Ann Ozsivadjian, Principal Clinical Psychologist, Independent Practice and Evelina London, Children’s Hospital. Talk on a course.