Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

How does ADHD affect school-age children?

| Inattention | Impulsivity | Hyperactivity |

| Does not pay attention,

Does not listen,

Easily distracted |

Interrupts frequently,

Does not wait for their turn,

Talks excessively, |

Always on the go

Fidgets almost constantly Cannot sit still |

But that is just the tip of the iceberg – there are many other hidden problems!

The (not so) hidden problems of ADHD

- Poor working memory

- Learning difficulties

- Behaviour problems: oppositional behaviour

- Poor risk awareness

- Poor sleep pattern

- Disorganised

Important considerations

Developmental: young children are typically more active. For a diagnosis of ADHD, the degree of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity should be more than expected for the child’s age.

Duration: Transient behaviours come and go depending on changes in social circumstances. For a diagnosis of ADHD, the symptoms ought to have persisted for six months or more.

Other explanation: Consider other reasons for similar behaviour:

- Mismatch of learning ability and academic activity

- Autism

- Lack of motivation

- Poor hearing

- Anxiety, depression

- Neglect, abuse, bullying

Some medical/mental health conditions that can cause similar behaviour:

- thyroid problems

- clinical anxiety or depression

- emotional traumas and sudden life changes

- lead poisoning

- undetected seizures

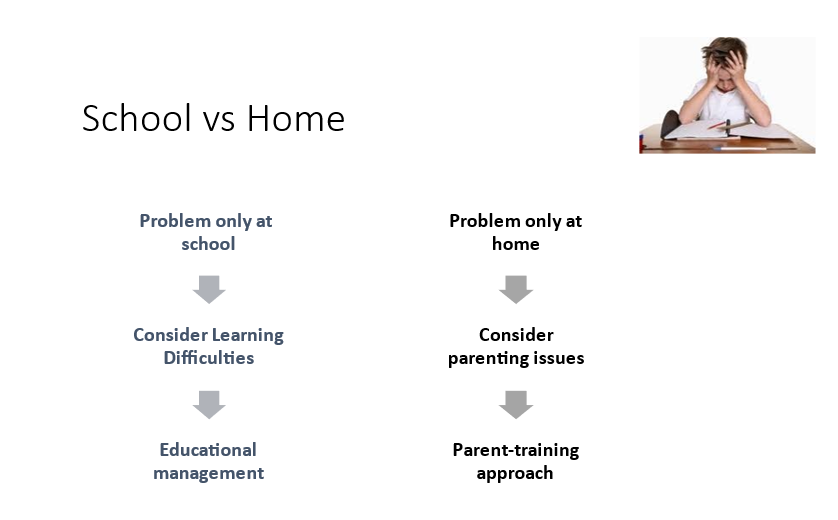

What if the child is only hyperactive at school or home?

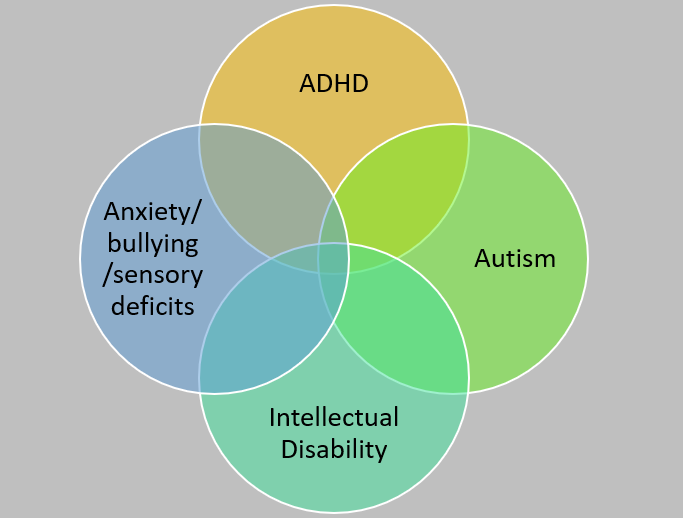

Are similar behavioural features seen in other conditions?

Yes, other difficulties, as shown in the image below, also show some of the features of ADHD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and ADHD

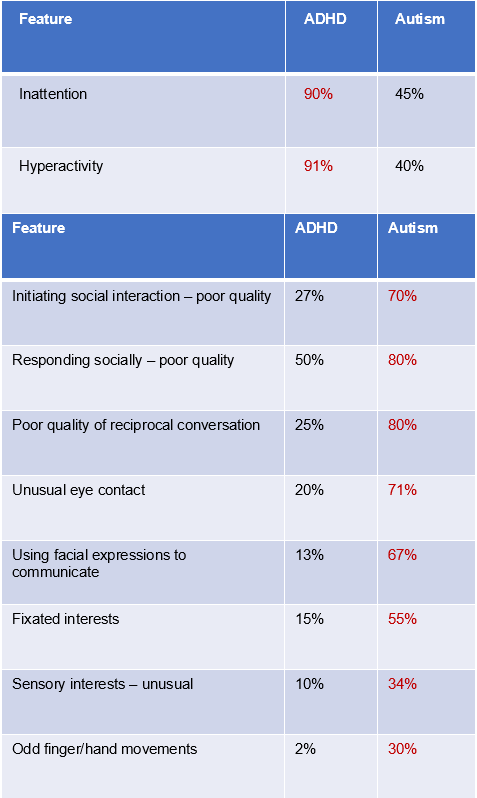

Children with autism have a poor sense of social situations and appropriate social behaviour, and their behaviour may sometimes look like ADHD. Conversely, children with ADHD are often impulsive and disinhibited and may have poor social behaviour. These two conditions also share some other behaviours, as shown in the table below. However, turn-taking and imaginative play are often (not always) intact in ADHD and often (not always) lacking in ASD.

Source:

1. Craig, F., Lamanna, A.L., Margari, F., Matera, E., Simone, M. and Margari, L., 2015. Overlap between autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: searching for distinctive/common clinical features. Autism research, 8(3), pp.328-337.

2. Grzadzinski, R., Dick, C., Lord, C. and Bishop, S., 2016. Parent-reported and clinician-observed autism spectrum disorder (ASD) symptoms in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): implications for practice under DSM-5. Molecular autism, 7(1), pp.1-12.

What causes ADHD?

ADHD is a genetic AND environmental condition. It is a genetic condition that is made worse by certain environmental risk factors:

- During then pregnancy and at birth: maternal stress and illness, and birth complications such as prematurity.

- By sustained neglect and abuse of the child

What can happen if a child with ADHD is not supported?

The outcomes of children with ADHD depend on:

- The severity of ADHD: Not just how many features of ADHD are present but how significantly or not they affect the child’s learning, behaviour and socialising at home and the school.

- Other difficulties that the child may have: ADHD often combines with the impact of some additional problems that the child may have, such as learning difficulties, reading difficulties, behavioural issues, anxiety, and sleep problems.

- Availability of or a lack of social support for the child and the family: children from well-resourced and supported families learn to manage their difficulties created by ADHD and have better outcomes than children from poorly supported families.

- One must also remember that children with ADHD have a high risk of accidents.

In general, children with ADHD are vulnerable to:

- Underachieving at school or being excluded from education

- Developing emotional problems, such as anxiety and depression, and having low self-esteem

- Being teased and bullied and becoming socially isolated

- Taking part in high risk anti-social or criminal activities, including drug and alcohol intake or putting themselves or others at the risk of physical harm.

Supportive strategies

Understanding and acceptance

Generally speaking, children with ADHD are seen as ‘trouble’ and are not liked by teachers and carers. They are often told off and punished, reprimanded and excluded, or simply ignored. So it is no wonder that many of them become increasingly defiant and hostile. And with time, they just give up; they simply want to be out of that environment and start truanting and missing school.

There is good evidence to suggest that children are affected by the way we look at them. And it is no wonder because our behaviour, approach, and the way we work with children are affected by how we look at them. So, it makes sense that we reflect on our attitude and develop a sense of understanding and a way of looking at the positive aspects of the child.

We have to see the child as someone who is struggling in coping with the difficulties they have and that they may not understand what they’re dealing with. It affects their perception – how they see things, how they respond, and how they behave.

Our compassion towards the child will be evident in our looks and voice, which is the beginning of the change.

We can also see the child as having some strengths; we can see the child’s distractedness as a high level of awareness, restlessness as a sign of energy and liveliness, the going off-topic as their individuality, the interruptions as their enthusiasm, and being self-absorbed as their thoughtfulness. It may not always be easy, but an attempt to look at the child positively creates chances to reward the child and build on the child’s strength rather than continually pointing to their deficits and undermining their sense of self-confidence.

Helpful classroom strategies

- Assign work that suits the student’s skill level. For example, children with ADHD will avoid classwork that is too difficult or too long.

- Set achievable goals – both over and under expectations stifle motivation.

- Offer choices. Children with ADHD who are given options for completing an activity produce more work, are more compliant and act less negative. Therefore, offer a list of activity choices; for example, practising spelling tasks may give options of writing words on flashcards or air-writing words.

- Reduce auditory distractions by seating the child with ADHD in a quieter place. Use low-level music, noise-cancelling headphones, or earplugs if the child tolerates.

- Reduce visual distraction by appropriate positioning in the room, such as facing towards a wall.

- Use bright colours or cue cards to attract attention to a task.

- Please don’t force them to still because they can’t. Instead, give some space and time for their hyperactivity: give them small breaks between tasks for them to move around. And make them aware that they can use their time and their space to move, jump, fidget, and if they want, sing a song – this way, you will help them gain control over their needs.

- It’s hard to stop children with ADHD from fiddling and fidgeting. So, be proactive rather than reactive to this. It is a good idea to give them something to fiddle with, such as spinners, squeezable balls, tangle toys or small building blocks, of course, as discussed in the point above, with some plan about when and where – with the idea of their own space and their own time.

Supporting organising and working memory difficulties

- Encourage the child to connect information or concepts being presented, for example, connecting an idea with an emotion or an event.

- Repeat directions individually; name the child as you give a direction.

- Use visual maps to make information more stable and connected.

- Colour code for work and the homework diary.

- Use flashcards for cueing or prompting the child.

- Mnemonics can also help remember important facts.

- Make reminders and lists. Using sticky notes, diaries, and taping instructions to their book bags can serve as memory prompts.

- Help children draw up a checklist of things to do. As they grow older, lists can make their lives much more manageable.

Seating in the classroom

Students with ADHD tend to get overstimulated when working in group situations. Try the following:

- Pair them with less distractible students who are likely to follow the teacher’s instructions.

- Seat them near the front of the classroom, away from doors, windows and other distractions or in an area of the room which may be more suitable.

- It is often better to sit them at a single desk or a paired desk within the primary classroom.

- There should also be another area or workstation set up facing the wall and away from the primary classroom area to learn as needed.

Keeping them focussed

- Keep your educational content stimulating and varied.

- Children with ADHD tend to respond better to concrete learning experiences. Therefore, connect ideas with real-life situations as much as possible.

- Encourage children to tell you if they do not understand what they are meant to be doing.

- Reinforce instructions as many times as possible and remain positive at all times.

Encouraging attention

- Give a brief outline of the lesson at the beginning.

- Try to include a variety of activities in the lesson.

- Break the lesson into short chunks.

- Allow alternative ways of recording information, such as using a laptop.

- In the workbooks, give only one or two activities per page.

- Give visual and verbal prompts. Use particular cue phrases, such as “doing good so far”, to prompt and maintain attention. Use gestures and symbols as prompts, e.g. picture of sitting, listening and looking.

- Focus the child’s attention before giving instructions, e.g. “Ravi,….listen….”

- Give positive feedback, e.g. “good listening”,

- Remember to use an appropriate level of language for the child. Generally, use short and simple phrases while giving instructions. Check that the child has understood the information. Ask the child to explain what he has to do. If necessary, show the child what to do rather than repeating verbal instructions.

Homework

It takes a student with ADHD about three times as long to do the same assignment in the home environment compared to the school setting. It can be the final straw for many children with ADHD that puts them off school and takes them in the direction of truanting or refusing to go to school. Consider the following to help the child cope:

- Is the homework essential? If not, change it to some other activity or break it into small parts.

- Can the style of providing answers be made easier for the child, such as answering multiple-choice questions rather than writing an essay?

- Can the child be given some extra incentives for doing the homework?

- Can the student stay at the school for a bit longer to complete the work rather than taking it home to do it?

- Can the child use some technology to assist in completing the homework?

Using clear communication to increase compliance

- Children with ADHD respond better to short, clear and direct communication. Here are some examples worth considering:

- Always address the child by name.

- Try to make eye contact before saying anything, wherever possible.

- Speak clearly in an even tone; keep your voice calm!

- Don’t ask why, rather say (for example) what should they be doing and when, for example, “Dino, when you have done —– then you can go”.

- Say more of what they should be doing and less of what they should not be doing.

Dealing with outbursts

Children with ADHD have more than their fair share of explosive outbursts. They make mistakes, don’t finish what they set out to do, others don’t look very kindly at them, and the frustration builds up. Sometimes, only a minor reason is enough to light the fuse.

At those moments, there is very little one can do with the child, but there is a lot that one can do with themselves.

First of all, one has to stay calm and show that you’re not wobbled and still in charge. That feeling of calmness has an impact, and it helps the child know that someone else is in control of the situation. Your mood shows on your face and in your body, so be mindful of your expressions, voice, and body language and remain non-aggressive. Try to look at and analyse your mood, and don’t take it personally.

Try not to talk too much – the child is probably not listening to you. And there is absolutely no point in trying to teach any good behaviour or reprimanding the child, hoping that that might have some effect – no, this is not the moment to teach anything.

Have a plan because this, as you know, was going to happen. Also, have an ‘escape route’ for the child and a safe calming zone. The idea of giving them space is to have a less stimulating place. You can use it as an escape route for them when they have an outburst, but you can also use it in a structured way or in a planned way rather than as a punishment or reward. Giving it a familiar name might help – it might be a ‘thinking space.

Once the storm is over, then that is the time to start working on some preventative strategies. Be on the lookout for good behaviour, and praise the child in their earshot as soon as that happens. Yes, there will be moments when you will have to say that what they’re doing or what they did was not right but try to have a ratio of four praise to one criticism; remember this 4:1 ratio.

Set boundaries and have reminders and prompts. Be assertive with the child without being aggressive. Never be sarcastic. Suggest ways of doing things right rather than asking why they did it wrong. And have your rewards ready. Praise is the best reward, but a token reward system can work wonders for children older than five years. Use a visual structure for tokens. Always only give the reward as promised, and when the child achieves something, never do it beforehand because that will be bribing, and it will backfire like anything!

Finally, remember, do everything in the context of a positive affectionate relationship. Changing behaviour is about changing your mood and theirs. And it works.

Supporting peer interactions

Children with ADHD are not much liked, even by their peers. They are impulsive, interrupt and intrude, have a poor sense of personal space, and are accident-prone, which puts off many of their peers. All that makes them an easy target for teasing and bullying. Some of them are also rather too sensitive to being teased by others. None of this helps either in group activities or in forming friendships.

The following strategies help overcome the barriers in their socialising:

- if possible, work with another child to become a buddy with a child with ADHD. It may take some encouraging, supporting, explaining, prompting, and rewarding, but it will pay off if it works. However, it may become too much for one child to be the body, so be ready to replace/rotate the child with another one. You will only increase the probability of success in a small group work this way.

- Start with some supervised small group activities. Prepare the child with ADHD in advance with some prompt and support, gradually withdrawing support to let the child experience real-life interactions with peers.

- It is always worth explaining to other children in a supportive and compassionate way about the difficulties that children with ADHD face and how best to get along with them. Do it before some field activity and reward the group for their understanding and good behaviour.

- It may also be worthwhile teaching the child with ADHD some social skills such as controlling their impulses. It is helpful to use the example of the traffic light system and help the child monitor their behaviour. Let them tell their success stories of the day and reward them for those stories.

- Remember, it is not just you, the class teacher, who is involved here. Share your understanding experience and plan with parents and the support staff. The child needs to be surrounded with the right approach for it to become effective.

Working with parents

Parents need to know the experience of the school, the understanding that the school has gathered, and the way forward. Talking to parents needs to be done in a strength-based way and almost continuously pointing to the child’s best interest. Parents often become defensive when their school points to the defects are deficits in the child, and places the responsibility of sorting it out on them. Any plan for support needs to be a shared one between this school and parents. Keep the parents posted, not just about the wrong things, not just about the difficulties but about achievements, no matter how small, and praise the parents for doing their part; they are the ones who will make a difference.

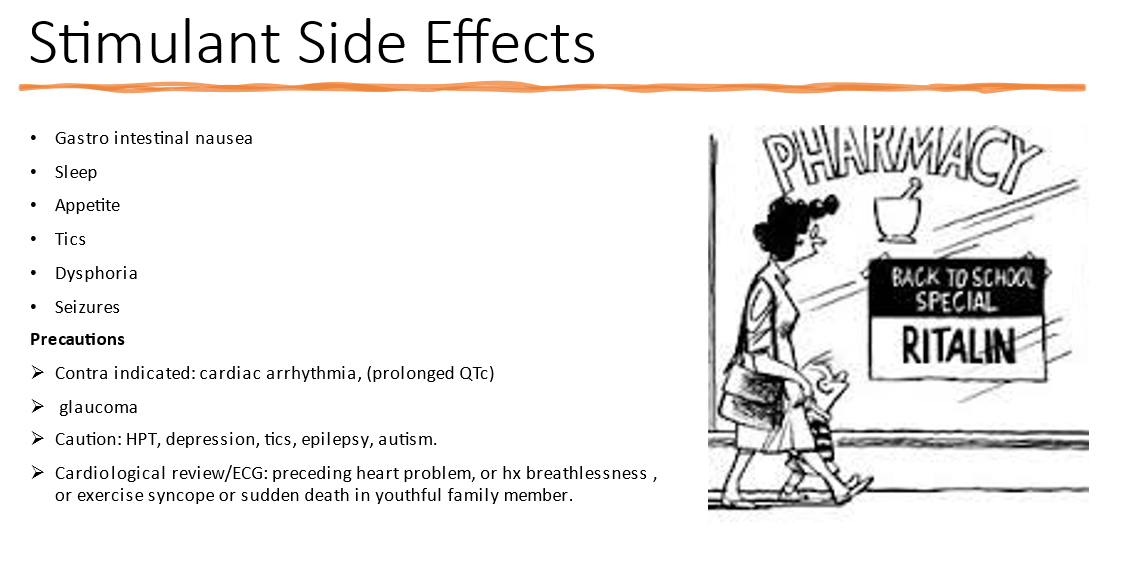

Medicines and ADHD

There are medicines available to treat ADHD. They should only be given to children with severe ADHD when other support measures at home and school have been tried. Rushing to medicate the child can be a big mistake because the medicines do not make much of a difference in about half of the children. So it is back down to the school and parents again. Also, there are side effects to medicines, and some of the side effects can be serious. So it is not something that should be started without proper consideration of the whole situation and the consultation with a paediatrician who is empathetic towards children. I’m afraid there is a trend in medicalising the attention needs of children, and some of the medicines currently being used are outright dangerous, and the way they are being used is outright callous. So, please, do not see it as a quick or an easy option. A lot can be done to help the child if the school and parents work together; if they hold their nerves and support each other, then there is a way forward.