Autism and Behaviour

Children who behave well, get on better with others. Many children with autism have behavioural difficulties that affect their socialising and learning. Reducing these difficulties makes it easier for parents, teachers and others to look after and help them. Improving behaviour is not just children’s responsibility, parents and teachers also contribute to it. Knowing what to do, how to do, and learning the skills and methods can help parents and teachers in improving children’s behaviour.

Why do children with autism have difficult behaviour?

Some factors affect the behaviour of all children:

– All children want attention. They want their demands to be met promptly. If for some reason, this does not happen to their satisfaction, they tend to display difficult behaviour to achieve what they want.

– Sometimes, children try to get what they want by displaying unwanted behaviour. Most parents give in to the demands of their child when the behaviour becomes too much of a trouble for them. It is no wonder that children then learn this way of getting their demands met.

– Children often display unwanted behaviour when they need to get out of a stressful or difficult situation.

– Children do not fully understand others’ feelings, thinking or situation, which increases the chances of their behaviour not being right for the situation.

– Children’s control of their emotions and behaviour is underdeveloped. That is why their responses are often angry and disproportionate.

– Children tend to repeat their behaviour if they get a certain reaction from others (laughing at their behaviour, shouting at them, getting angry with them or hitting them) or if others give in to their demands.

Behaviour difficulties are more common in children with autism because:

– Autism affects children’s ability to understand others’ intentions, desires and situations. This lack of understanding creates anxiety and frustration and adversely affects their behaviour.

– Difficulty in communicating one’s needs, desires and feelings can be an immense source of frustration for children with autism. If we could magically change their behaviour into words, they might be saying things like:

● “I’m scared/anxious” or “I want to get out of here” or “I don’t want to do this anymore”

● “I’m bored” or “I don’t know what to do next”

● “I really hate that noise … turn it off.”

● “I’m very hungry/thirsty.”

● “I have a terrible headache/tummy ache.”

● “Please don’t move my things, I need them to be where they always have been. It really upsets me.”

– Hypersensitivity to some aspect of the environment (to a crowded space, physical contact, light or sounds) creates anxiety and stress, which makes the behaviour worse.

– Difficulties in regulating their emotions: The ‘thermostat’ that controls how far one goes with an emotional reaction, is poorly developed in children with developmental difficulties; it triggers a minor issue into a major reaction and difficult behaviour.

– Children with autism have difficulty understanding others’ interests and perspectives, social boundaries and personal space, and how to behave appropriately in different social situations.

– For most children with Autism, it is extremely difficult to shift from one idea or activity to another Idea or a new activity or change a plan, even though it may be more suitable or appropriate. Defiance is often an expression of their rigidity.

– Anxiety is common in autism. It makes the child feel stressed or scared and their behaviour is more likely to be volatile.

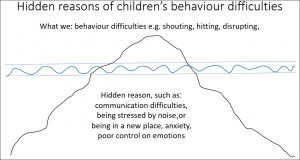

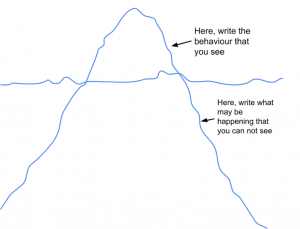

As it is true for all children, children with autism always have a reason behind the behaviour. While the behaviour is visible to others, its reasons are often hidden like the hidden part of an iceberg. It requires careful observations and understanding of their situation to work out the reasons behind their behaviour.

It must be very clear that while the issues related to Autism may explain why a child has difficult behaviour, they are not an excuse for the unwanted behaviour to continue. Their behaviour can be improved with the right understanding and approach.

Managing behaviour difficulties of children with autism

There are five essential steps for reducing difficult behaviour

1. Reducing the conditions or situations that trigger or worsen unwanted behaviours

2. Creating a positive relationship with the child

3. Increasing the child’s “good” or “right” behaviours

4. Teaching new “good” or “right” behaviours to the child

5. Managing the wrong or unwanted behaviour

Over-focusing on the wrong or unwanted behaviour could reduce such behaviour for a short time, but it increases the possibility of such behaviour re-emerging or a new wrong or unwanted behaviour starting.

Initially, you would have to understand and practice each of these steps separately. However, after some time, this will become your way of working with your child in all everyday situations, which would make it a lot easier and it would also maintain your child’s behaviour.

Reducing the conditions or situations that trigger or worsen unwanted behaviours

1. Can the child communicate his needs? Not being able to communicate needs is a common reason for children becoming frustrated. Help the child learn suitable means of communication, such as signs, symbols or pictures for conveying essential needs.

2. Does the child understand what others say? Keep your language very simple, give instructions in small simple parts, use gestures and facial expressions and consider using signs/symbols to improve the child’s understanding.

3. Does the child understand what needs to be done and when? does the child become anxious when starting any new activity? Use a visual timetable to explain the sequence of events, daily routines and what needs to be done when. Keep the visual timetable available to the child to make it simpler for the child to follow it. Give the child some time for shifting from one activity to another (use counting, clapping or singing little rhymes). This would reduce the level of anxiety, make the child calmer and make it easier for the child to shift activities or to start a new activity.

4. Does the child know how to ask for help? children often get frustrated with not being able to do what they need or want to do. They should know an easy way of getting help verbally, by using gestures or expressions or by using symbols or signs.

5. Does the child become upset on hearing certain sounds or loud noises? Try reducing background sounds and noise or try getting the child to use a headphone. See: Helping a child with hypersensitivities.

6. Does the child gets upset by some other aspect of the situation? Children with autism don’t like people standing around and watching them. Try to make the environment free of such interruptions and give the child some time and space to relax. Teach the child Ways of relaxing and becoming calm.

7. If the child is tired or stressed, let the child rest first.

You should also make everyone related to the child aware of these issues and ways of reducing the stress for the child.

Creating a positive relationship with the child

Although there is always a mutual bond of love between parents and children, creating a positive relationship needs some effort. Children behave and learn better in an environment where such a positive relationship exists. Parents provide a model for children to learn from. When parents act positively children respond positively, and their behaviour and learning improve.

How to create a positive relationship?

To create a positive relationship, you need to join and engage in activities with the child. Such joining in requires:

– your full availability and attention,

– your full awareness, and

– use of the positive ways of working with the child

It is practically not possible to do this all the time, and it is not required either. Parents are busy, have a lot of things to do and children also need their own time. Initially, you should try to find 3or 4 such times in a day when you can engage with your child without interruption. Once you are used to this way of engaging, it would become easy for you to do so at other times too.

A method for joining in with the child:

– Let the child take the lead in choosing an activity based on his or her interests. Do not direct the child, do not impose your wishes on the child and do not ask questions. Children often like repeating some activities because they enjoy doing these activities and they also learn from such repetitions. Have patience and engage with what the child is doing, do not try to redirect the child to do something else.

– Sit close to the child, give your full attention, listen to what the child says and try to imitate what the child does.

– Describe, in easy language, what the child does, for example, “You have made a tower”, “the doll likes the food”.

– If something goes wrong, support the child “never mind, this happens, let’s try again”.

– Don’t find flaws, only give praise, for example, “Raju, this is very nice!”, “you are great”, “that is a great idea”, “you are the best”. Show enthusiasm in your speech and expressions.

– Praise the child’s play, drawing, activity or behaviour in front of others.

– At least at the beginning, choose a time for effective engagement with the child when you’re not in a rush or distracted. Once you have practised these activities, it will become your second nature and you would be able to join in with the child as part of your day to day work and activities.

Such effective engagement in activities would improve the child’s self-confidence. They would pay better attention to what you say. Their language and social interaction would improve and their interest in others would increase.

How do children learn good behaviour?

1. Children learn behaviour from their experience, particularly when they get something, like a reward out of it. Here, the reward does not mean the same as getting something on winning a competition but a good experience, such as being praised, given attention or affection. Getting what they want, whether it is a toy, an object or permission to do what they want to do motivates children to behave in a certain way. When a behaviour does not result in a good experience or reward, that behaviour, good or bad, tends to decrease.

2. The reward needs to be given immediately for the child to make a connection between the behaviour and the reward. At least initially, it also needs to be given every time after the right behaviour. In time, even intermittent rewarding can reinforce the learnt behaviour.

3. When being taught a new behaviour, children must clearly understand what is expected – what is it that they are required to do – must be made clear to them

4. It is easier to learn a new behaviour if it is part of the sequence of a regularly occurring activity, such as ‘tidying up toys’ is part of the activity ‘playing with toys.

5. Regular practice is the best way to learn anything. Children need opportunities to practice the new behaviour.

6. Children also learn new behaviour by observing others. Parents’ and carers’ behaviour is a model for them to learn from.

Increasing the child’s “good” or “right” behaviours

Improving children’s good behaviour, helps them learn better, improves their social interaction with others and improves the cohesion in the family.

Every child, even the one who frequently misbehaves, does some things right in a day, which often go unnoticed. These occasional moments of “goodness” can be increased by giving the child attention and praise. If done properly, this can be an effective way of improving the child’s overall behaviour. Such improvements have a long-lasting effect on children’s behaviour. Once you have learnt the method of increasing children’s good behaviour, you can make that your way of working with the child and use it with ease in every interaction.

Preparations:

Watch your child carefully, think about his behaviour and make two lists:

List 1: The good behaviours that your child shows, even if occasionally:

Such behaviours often go unnoticed. You should pay attention to the list of little behaviours mentioned below and think about whether your child shows some of them at some time during the day.

1) Playing or doing some activity by himself

2) Sitting beside you

3) Playing with you

4) Looking at the pictures in a book

5) Listening to a story

6) Asking for something from you using language or gestures

7) Giving something to others spontaneously or when asked

8) Saying hello or greeting others

9) Showing affection towards others

10) Eating food properly

11) Following instructions

List 2: Items or activities that your child likes or finds interesting

Parents know their child’s likes and dislikes. You and other carers could use items or activities from this list to motivate or reward the child. The following examples will help you draw your list:

1) First, don’t forget the most important reward: Children love getting attention, being praised and receiving affection. Think, how you praise your child and how you show your affection towards them. Your voice, your expressions and your behaviour must make it obvious that you are showing appreciation and affection.

2) Using some stickers or pictures, such as ‘golden stars’: Children love such a reward. These can be made easily and given freely to the child. You could use a calendar to stick a star on the day when the child has shown good behaviour. This would help the whole family in praising the child – whoever saw the calendar would say “Wow, your behaviour has been really good today”. It can also be used to motivate the child: “If you win 7 stars then you will get —— as a reward”.

3) Any toy or play activity that the child really likes can be used as a reward for the child’s good work or activity “you’ve done so well today, you can play with this toy”

4) Giving the child a book or reading a story as a reward

5) Giving the child some food that he loves, as a reward

6) Singing a song or playing some music that the child likes

7) Doing the child’s preferred activities, such as some outdoor or indoor game

Activity: encouraging the child’s good behaviour

Use the following sequence:

a. Bring the list of the child’s good behaviours to the attention of the whole family and other carers. Always keep your eyes open for these behaviours.

b. Whenever anyone notices any good behaviour:

– Give praise and affection to the child. This will also increase the child’s self-confidence and social skills.

– Give attention to the following when giving praise and affection:

– Use the child’s name when praising him or her. For example, “Raju, you were playing really well/ Good asking / Well done for giving / you ate your food really well”.

– Tell the child that you really liked what he did

– While praising, be in front of the child and give your full attention

– Share the praise with others when the child is around

c. Include the whole family in this process to increase the opportunities for such interactions

d. When motivating the child to increase behaviours that only occur when the child is doing activities of his interests, rewards from the second list can be used.

Ways of rewarding children

There are two ways of rewarding children:

1. Giving a reward immediately after some good behaviour

2. Giving a reward in a planned way, for example giving the child 1 point for every good behaviour and then giving a reward when the child accumulates 10 points. Usually, this can be done when the child is 3 to 4 years or older. This way of rewarding motivates children and helps them learn to wait for the reward.

Pay attention to the following when giving rewards in a planned way:

a. Make only one such scheme or plan at any one time. Explain it clearly to the child, if required, use pictures, symbols or a visual timetable to explain.

b. The expected behaviour should be such that the child can do.

c. The reward should be such that the child likes it.

d. Give the reward as planned and combine it with praise.

e. Only give the reward once the expected behaviour has happened; don’t give the reward first and expect the good behaviour to happen after it.

Teaching children new “good” or “right” behaviours

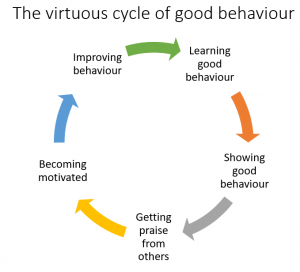

Using the right method, behaviour can be taught to a child. Once a child learns good behaviour, they are more likely to use it when prompted and encouraged. When the child shows the right behaviour, they are praised for it. When praised, the child gains self-confidence and becomes motivated to behave in the same way again. This sets up a virtuous cycle of learning good behaviour that has a lasting effect on the child’s behaviour and on the overall family functioning.

The sequence for teaching a new behaviour

1: Finding time: Initially, you would have to practice how to teach a new behaviour, it’ll be easier if you choose two or three times during the day when you have few or no distractions.

Once you have practised and learnt the method, you’d be able to use it easily, anytime during your daily routines.

+

2: Work on Reducing the conditions or situations which trigger or worsen unwanted behaviours to make it easier for the child to learn.

+

3: Choose the behaviour that you want to teach your child, for example, you may want to teach the child how to tidy up the toys after a play session. It may help to choose a behaviour by looking at List 1 that you had prepared earlier.

+

4: Choose a task or an activity that includes the behaviour that you have chosen. It is much better to work on the whole activity than only on one isolated behaviour.

The sequence for teaching the child behaviour that is part of an activity:

Using the activity ‘playing with toys’ as an example:

1: It will be better to plan this activity in 4 parts:

1) Taking toys out from a bag or a box 2) Playing with the toys 3) Tidying up the toys 4) Moving on to another task or activity (it will help if this task or activity is also of interest to the child)

2: Use a visual timetable to explain the sequence of the above four parts to the child.

[ Keep the situation in your control, only have things related to the activity in front of you and keep the rest away in a bag or a box]

3: Use words, symbols or pictures to explain to the child the sequence of moving on to the next task once finished playing.

4: Be engaged with the child in the play. When the playtime is finished, use words or gestures to say “playtime finished, tidy up time”; use a visual timetable to communicate this if required.

5: Get the child’s attention, and model by putting one or two toys in the box or in the bag. Wait for 5 seconds and look at the child expectantly and encouragingly.

6: If the child does not follow, repeat your modelling. Wait for 5 seconds. Prompt the Child by holding the child’s hand and encouraging at the same time. Wait for 5 seconds and look at the child expectantly and encouragingly.

7: Whenever the child does the expected behaviour, offer praise by naming the child and the behaviour, for example, “Raju, you tidied up the toys really well.”

8: Use the visual timetable to help the child to move on to the next task.

9: Use every opportunity to praise the child in front of others “Today Raju tidied up really well.”

10: Inform and include the rest of the family and others working with the child to practice this behaviour.

How to model good behaviour to teach it to your child?

Children learn both good and bad behaviour from others by watching them.

If you want to model behaviour for your child to learn, first make sure of the following three things:

1. The child should be able to pay attention to you

2. The child should be able to imitate you

3. You should have a positive relationship with your child

How to strengthen your child’s ability to pay attention to you and to imitate your activities?

– Play with the child

– While engaging with the child, take turns and imitate the child’s activity (don’t make fun of the child) and encourage the child to imitate yours

– Create enjoyable activities encouraging the child to imitate your gestures and expressions

Use Creating a positive relationship with your child to strengthen your relationship.

Once you’re comfortable, that your child has all the above 3 abilities, then use the following sequence:

– Choose a time when the child is calm

– Get your child’s attention and model the activity to be learnt (for example, greeting others or brushing teeth)

– Wait for 5 seconds and repeat your modelling

– Physically prompt the child by holding the child’s hands

– Praise the child as soon as he attempts to copy the behaviour or does it on prompting. Do not point out any flaws.

– Practice it repeatedly, each time giving a little bit less prompting and support

– Continue to praise the child for making the effort.

Some activities need to be taught in steps, for example:

For:

– Asking for help using a word, symbol or sign

– Saying no, using a word, symbol or sign, when the child doesn’t want to do something

The child needs to be taught:

1. when to do it

2. how to do it

These steps are best taught using a visual timetable, modelling and prompting. Once the child has learnt these behaviours, he would need to be given full attention to asking or for saying no.

How to help children in doing routine activities independently?

A good way of getting children to do some activities independently is to teach them some routines with fixed sequences. Children with autism find it easier to do routines with fixed sequences. One can use routines for activities that happen many times a day or in a similar way every day, such as having a meal, playing with toys, getting ready for school or getting ready for bed. It becomes much easier for children to cooperate once they get used to routines.

One part at a time

First, divide each routine into small parts and then teach one part at a time, for example:

– Sitting at the right place to have food + eating food properly

– Bringing the Toy Box or bag + Playing with the toys + tidying up the toys

– Changing clothes for getting ready for going to bed + brushing teeth + lying in bed and listening to a story

– Brushing teeth has four steps: 1) Washing the toothbrush 2) putting toothpaste on the toothbrush 3) brushing teeth 4) Rinsing the mouth with water

Set up some ground rules

It helps to make some ground rules (1, or maximum 2), for example, no hitting and no throwing of things. Write these rules on paper or a poster, use some drawings or pictures and remind the child of these ground rules every time a routine is practised.

Activity:

– Use symbols, drawings or pictures to make visual timetables for each part of the activity

– Use this visual timetable to explain each part to the child, one at a time.

– Use modelling, prompting and encouraging to teach each part

– Praise the child for completing each part

– Once the child learns each part, explain the sequence using symbols, drawings or pictures

– Use modelling, prompting and encouraging to do the whole activity together

– Praise the child for doing the whole activity

Getting children to follow instructions

No child follows every instruction given by their parents, that is normal! However, some situations make it harder for children to do as they’re told.

Paying attention to the following would help you improve the child’s positive response to instructions:

These factors make it harder for children to comply:

– The child not understanding the instruction:

Make your language simple and give instructions in small parts. If required, use signs, symbols or pictures.

– Children who do not have a positive relationship with their parents may not follow the instructions. See developing a positive relationship with your child

Doing the following improves compliance:

– To start with, you want the child to practice following instructions. Initially, give instructions about tasks that the child would want to do. The child would develop a habit of following instructions.

– As soon as the child follows the instruction, offer praise. Praise the child’s behaviour in front of others. Do not criticise the child for not following your instructions.

– Think before giving an instruction: do I really need to give this instruction. Only give the instruction that is really needed. Don’t give too many instructions.

– If you feel that the child is in a hurry or is unlikely to follow the instruction for some other reason, then don’t give it.

– First, get your child’s attention towards you and then speak in a simple and clear language.

– Don’t sound angry.

– If there is a reason for giving the instruction, then say that reason first (We are going out and it is time to tidy up your toys).

– Don’t make your instructions negative (don’t do this, don’t do that). Try using a positive tone (now you do —-).

– If the child is doing something else, give a little time for the child to shift to do another task (You can do —-for five more minutes and then do —–).

– Sometimes, it is worth giving a little time for the child to process and follow your instruction, have patience!

– Once you have given instruction then try to stick to it; changing rules and instructions for your convenience do not lead to good learning about following instructions.

– If you have promised a reward to motivate the child, then you must give the reward once the instruction is followed.

Reducing unwanted behaviours

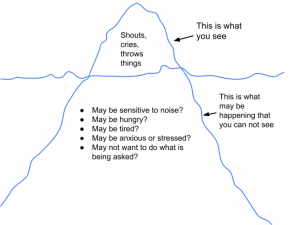

Step 1: Focus on one behaviour at a time to find out the likely causes of the wrong or unwanted behaviour – the iceberg activity

We see the wrong behaviour easily, but its cause – the reason behind it – is often hidden and are not obvious, like the hidden part of an iceberg. Such a reason is not an excuse for the wrong behaviour, but knowing it gives a way forward for helping the child to reduce such behaviour.

Use the chart below to carefully observe your child’s behaviour to understand what factors may be starting, contributing, or maintaining the behaviour. These observations will help you and other professionals in understanding and reducing or changing the difficult behaviour:

| Behaviour: |

| In what situation did the behaviour happen or what was the child doing when the behaviour started: playing, mealtime, bedtime, time of day, and what triggered the behaviour? |

|

|

| What was the behaviour: hitting, throwing, shouting, defiance, repetitive behaviour, being socially inappropriate, any other, and how long did it last? |

|

|

| What happened immediately after the behaviour. For example, the child got what he/she wanted, or the child was comforted or anything else you or someone did? |

|

|

| What the child may have gained from his behaviour, for example, attention from you or others in the family, his/her choice of thing or activity, becoming relaxed or avoiding what he/she doesn’t want to do (being with others or doing an activity)? |

|

|

Step 2: Now, look at the iceberg model and draw a similar one for the behaviour you are focusing on:

Now complete one ‘iceberg’ about your child:

Once you have carefully observed the behaviour for a few days, you should now be able to think about the following:

What makes your child’s behaviour worse?

What makes your child’s behaviour better?

Step 3:

- Use the Stress reduction Plan, you had prepared earlier, to address any of the reasons identified. Working on improving communication and attention, reducing anxiety, and altering the environment to suit the child will reduce or remove many unwanted behaviours.

-

Area of concern Consider including the following in the daily routine of the child Difficulty in communicating needs and feelings 1. Can the child convey needs and anything upsetting him/her? If not: – Organise use of appropriate means of communication, such as using gestures/signs or pictures.

– Help the child learn to use these means to express needs and feelings.

– Teach the child a way of asking for help and make sure that all around the child understand that method -practise it.

2. Does the child understand what others say to him/her? If not: – Use gestures and expressions to help the child understand.

– Keep your language quite simple.

– Use short sentences and divide an instruction in small chunks.

– Use signs/gestures and/or pictures.

Sensory difficulties Does the child become upset or anxious due to noise, light, or crowd? If yes: – Turn off or cover fluorescent lights when possible

– Minimise noise by speaking in a softer voice, turning down the volume for the radio or TV.

– Avoid using loud noises, such as shouting, clapping or whistling, to get the child’s attention.

– If the noise cannot be reduced, consider using earmuffs or headphones to reduce the sound perceived by the child.

– Give the child experience of handling and playing with different textures, for example, mixing dough, making sandcastles, counting beans or hand-painting to get used to multiple simultaneous sensations

Fears and anxieties Does the child become angry and upset by a change of situation or people? If yes: – Gradually supported exposure and preparation is the key to reducing the impact of the child’s fears and anxieties, for example, in a safe environment, when the child is with the mother or a known carer, first using a picture of the fear generating situation and talking about it.

– Introducing the child to the new place, one step at a time, for example, first showing the picture of the place, then just going to see the outside of the area and then going in briefly may help the child overcome the fear.

– First showing the child the fear-inducing things from a distance and then supporting the child by reassuring.

– Using something to distract the child in such situations may help; the distractor must be something that the child likes, like a squeezy ball or a picture book or a toy that the child likes.

– Giving the child some time and space to get over the stress.

Making change tolerable by increasing predictability Does the child get upset or anxious by change of situation or starting a new activity? If yes: – Prepare your child for any change in the situation by using . Pictures in a sequence to show the child what to expect

– Creating routines so that the situations become predictable for the child

– Explaining to the child what is going to happen next or after some time. Using activities such as counting to five or clapping hands to indicate change and practising these activities.

Attention and activity level Does the child find it hard to pay attention? Is the child overactive? – Do regular and varied fun physical activities with the child, such as running, jumping, moving stuff, lifting weight, and playing on swings. – For a child who dislikes physical activities, starting with a brief fun routine of a chasing or ball game, and gradually increasing the time, may help.

– For a child who finds it difficult to sit still, start with doing an activity that the child likes initially for a brief period, such as looking at a picture book, keeping the general tone and environment calm. Gradually increase the time; reward and praise the child for every increase of a minute.

General calming measures General stress-reducing measure for all children with autism – Help the child learn to relax by practising calming routines, such as: o Slowly counting to 10

o Taking five long breaths

o Listening to music

o Taking short breaks from activities

o Lying down and relaxing the whole body

– Reduce the impact of stress on the child by:

o Getting the child to do regular physical exercise for at least 30 minutes a day

o Making a calming sleeping routine: avoiding exciting activities before bedtime, avoiding mobiles/TV before falling asleep, reading a book or listening to some calming music

- Keep working on Building Positive Behaviour you had learnt earlier.

- Also, consider seeking help for any health-related condition, such as poor sleep, any ear or tooth pain, constipation, tummy upset or any other cause of pain that may be causing the child to behave in a particular manner.

What to do when a child misbehaves?

First, do not react inappropriately:

If parents or carers show a wrong reaction (laughing, getting angry or saying something loudly or showing too many emotions/expressions) to some unwanted behaviour or give in to the child’s demand or let the child get away from doing a task that the child is required to do, then the wrong reaction works as a reward for the child and they learn to behave in that way.

Learn these golden rules of what not to do:

- Don’t become angry or shout at your child – that will only increase the bad behaviour

- Don’t laugh at your child’s unwanted behaviour or make fun of your child

- Don’t be harsh or force your child

- Don’t argue with your child

- Don’t give in to your child’s demands just because of his/her difficult behaviour

- Don’t be inconsistent: sometimes agreeing to your child demands and at other times refusing

- Don’t try to bribe your child – by giving rewards before the child has shown the right behaviour – rewards only work when they follow the right behaviour

- Don’t try to teach the right behaviour when your child is in the middle of showing bad behaviour

- Don’t criticise your child in front of others

- Never hit or hurt your child

The right way of responding to unwanted behaviour

You will need to think and plan your actions. You will also need to include the whole family in this plan; otherwise, different responses from family members will only make the situation worse.

Step 1:

- Choose one unwanted behaviour; you cannot work on all the wrong behaviours at the same time. Choose a behaviour that is harmful to the child or others, such as hitting or biting, or which bothers the child most.

- Have you tried to do something about correcting or reducing the reasons for this behaviour?

- Have you tried adapting the situation to suit the child or reducing the child’s stress?

- What would have been the right behaviour for your child to do in that situation? For example, instead of crying and getting angry, your child could have communicated needs or desires by using words, signs, or symbols, taking a rest if tired or communicating about being stressed.

- Have you tried teaching your child some of these right behaviours? Remember, you can only do that when the child is calm; practise them repeatedly so that the child can use them when needed.

Step 2: If you pick up early that your child is starting the unwanted behaviour: interrupt and redirect

- Try interrupting by redirecting your child to an activity of his interest (for example, a sensory activity) or to the desired action that you have been practising. You can only do this if the child has practised doing the right behaviour earlier; you cannot teach the correct behaviour when the child is upset.

- Keep ignoring the unwanted behaviour and help the child by giving prompts to show the desired behaviour

- Give praise and rewards if the child tries to show the desired behaviour

Step 3: If the unwanted behaviour occurs: convey disapproval

- Convey your disapproval, without showing any anger

-

- Get the child’s attention

- Say “No, don’t do that” or “stop” in a firm and calm voice and with facial expressions of displeasure

- Give about 10 seconds for the child to respond, stay calm

- If the child persists with unwanted behaviour, repeat displeasure. If the child continues with the unwanted behaviour, go to the next step.

Step 4: if the unwanted behaviour continues

- Remove your attention from the child (ignore the behaviour). You will need to ignore the child’s crying and all the expressions that go with it, not because you don’t love your child but because you want the behaviour to improve.

- Make sure the child is safe.

- While ignoring, you will need to involve yourself in doing some other activity

- Do not argue with your child or criticise the child. You are trying to remove your attention from the child and give a message that she/he does not get attention by doing the wrong behaviour.

- As soon as the child calms down, you will need to give your full attention to the child – you need to ignore the behaviour, not the child.

- Do not criticise this behaviour afterwards. Praise every good behaviour.

- Teach any right behaviour when the child is calm.

Step 5:

If the child becomes too upset:

- Try to calm the child without giving too much attention. Acknowledge the feelings without giving in to the child’s behaviour “ I know you are very upset but first calm down”,

- minimise your emotional response; don’t show much emotional expression

- don’t give in to the child’s demand

- don’t bribe or negotiate at this point

remain aware of the child’s and others’ safety, and act promptly if anyone is at risk of getting hurt

By applying this method, children’s behaviour can deteriorate for a few days before it starts improving. Be patient, hold your nerve and get help from others, but stick to the right methods, and you will have helped your child.

Three main types of behavioural crisis in children with autism:

1. Severe and prolonged tantrums

Tantrums occur either when the child’s wish is denied. Typically developing children also do it, but in autism, it is prolonged and severe. A tantrum is often a learnt behaviour – they watch others and try to get others’ attention – and giving in to it is never a good idea as it only reinforces the tantrum behaviour. Sometimes, the situation gets out of the child’s control because of their poor emotional regulation, and even they do not know how to turn off the tantrum!

Managing tantrums

- Stay calm. Your panic will only make the situation worse. Don’t cry or yell and keep your voice firm and steady; children are reassured by firmness.

- Catch it early: read early signals and try distracting the child to something of the child’s interest and which is calming for the child, for example, their choice of music or game.

- Show that you are aware that the child is upset by saying in a calm voice: “I know you are upset.”

- Remove attention, unless doing so would put the child at risk

- DO NOT give in or bribe the child

- DO NOT reason or argue

- Do NOT try to teach good behaviour at this time.

- Remain aware of the child’s and others’ safety, act promptly if anyone is at risk of getting hurt.

- Praise the child when the tantrum settles and practise the right behaviour. Do not criticise the child.

2. Meltdown

Meltdowns happen when the build-up of anxiety and stress crosses the limit of what the child’s system can put up with, and their pent-up stress boils over, causing prolonged crying and aggression. There is no particular purpose to this behaviour apart from releasing stress.

Unlike a tantrum, the child does not show any awareness of others’ reactions.

Managing a meltdown

- Stay calm. Your panic will only make the situation worse. Don’t cry or yell and keep your voice firm and steady; children are reassured by firmness.

- Catch it early: read early signals and try distracting the child to something of the child’s interest and which is calming for the child, for example, their choice of music or game.

- Show that you are aware that the child is upset by saying in a calm voice: “I know you are upset.”

- Help the child by removing demands from the child and reducing any sensory overload such as noise, such as moving to a calmer place.

- Use some practised calming method, such as a sensory toy or listening to music.

- Use a soothing method that you know works on your child, for example, hugging, touching, holding or singing.

- Some children may need to be left alone, removing stimulation and demands, in a safe and calm place, to calm down, but do not create prolonged isolation for the child.

- DO NOT criticise the child. DO NOT reason or argue. Do NOT try to teach good behaviour at this time.

- Talk about the incident after the child has settled, and only about how the child calmed down and settled, what would be unacceptable (hitting others or breaking things) and what she/he could do better in the future. Build a reward programme (giving stickers) for the child showing good behaviour in future. Don’t criticise the child.

- Remain aware of the child’s and others’ safety, act promptly if anyone is at risk of getting hurt

Taking the child to a hospital in such a situation may only make things worse; children with autism don’t react well to hospital environments. Medicines have almost no role in managing such situations. Trying to medicate children with autism by giving sedatives often makes them irritable and aggressive. If you have tried the above plan, worked on the behavioural improvement plan and still have serious issues with your child’s challenging behaviour, then take advice from a counsellor and a child psychiatrist.

| Remember, preventing is the best way of dealing with both these behaviours. Work on:

❏ Improving communication using symbols if required ❏ Practising alternative behaviours or favourite activities that could be used as replacements of demands, such as a sensory toy, music, reducing noise with headphones. Using a predictable plan will help the child too. ❏ Reducing stressful situations such as noise or crowd and creating frequent breaks or relaxing times. ❏ Teaching, practising and rewarding positive behaviours, such as asking, giving, showing, sharing |

You need to think through the above and individualise it for your child. Plan and share it with others and have it ready to use in the event of a crisis.

3. Shutdown (mental and physical inactivity)

Some children slow down in all their activities, such as talking to others, speaking, doing daily chores, and even eating food. Their body movements also decrease, and they often appear relaxed. It may also happen that at one time it seems that the child is shut down and at other times he feels fine. This situation may worsen if help is not provided.

Helping the child during the shutdown phase

- Is there a reason in the environment that is causing mental stress to the child?

- First, reduce such stress.

- Is the child under pressure due to any other reason, such as any change in school or expectations from him to work beyond his capacity?

- Reduce these reasons by meeting with the school

- Is any other child or elder taunting or bullying the child?

- Intervene to change this state.

- Is there a lack of a regular schedule in the child’s routine at home or at school?

- Create a routine for the child with the help of visual timetables.

- Help the child follow his routine.

- Is the child not getting enough mental encouragement?

- Play games with the child or do things that he is interested in, he can easily complete and for which he gets praise on completion.

- Do not allow the child to sit and watch TV or video throughout the day, encourage the child by making a routine of doing such tasks before and after more active work.

- Start the child’s routine with his or her favourite work.

- Make a routine of walking or playing outdoors with the child every day.

- Motivate the child to work, but at this stage reduce the decision-making burden on the child.

- Is the child able to get the support he needs?

- In this stage, the child needs 1–1 help; The child should have a good and sensitive relationship with such helpers.

- Is the child taking any medicine?

- Shutdown-like conditions often occur due to the ill effects of some medicines. Check the medicine by taking the help of a doctor, and if necessary, stop or change the medicine.

- Does the child know how to relax and reduce stress?

- Help the child to learn a plan to relax and reduce mental stress.

4. Self-injurious (hitting/biting self) behaviour

Such behaviour is extremely distressing for parents and makes it very hard to look after the child. Unfortunately, parents and teachers often react wrongly to such behaviour, which makes the situation worse.

Managing self-injurious behaviour

- Does the child often choose such behaviour when frustrated or distressed?

If yes,

-

- Modifying the environment to make it less stressful for the child

- Does your child have difficulty in communicating, understanding others, or expressing themselves?

If yes,

-

- Improve the child’s communication. This is the most common reason underlying such behaviour – make it a priority for you and the child.

- Does your child seem to be using such behaviour to get what they want or to reduce their boredom or to escape from a task that they don’t want to do?

If yes,

-

- Teach the child ways to convey their needs and desires

- Practise these ways when the child is calm,

- Encourage by rewarding whenever the child uses the right way of conveying needs or desires

- Does your child seem to do the self-injurious behaviours to generate certain sensations?

If yes,

-

- Consider giving the child other sensation generating toys and activities such as chewing, touching, stroking and sound/music.

- Create opportunities for the child to play with such material – the child may need help and encouragement in using sensory material.

- Does your child seem to do such behaviour for seeking attention from others?

If yes,

-

- Stop giving attention to such behaviour

- Instead, give the child a lot of attention and praise for any other alternative behaviour such as playing with a toy or a sensory activity.

Finally, increasing children’s existing good behaviours and teaching them alternative behaviour, through rewards and reinforcement, should decrease opportunities for indulging in self-injurious behaviours.

Self-stimulatory behaviour (stimming)

Some children with autism show repetitive behaviours such as flapping their hands, moving their hands or fingers, covering their ears, rocking their body, pacing up and down, biting or chewing objects or toys and sometimes even their fingers or hands and at times pinching their skin or pulling their hair. These behaviours are known as self-stimulatory behaviours or stimming.

What causes these behaviours?

There are several reasons for such behaviours to appear, and one or more of them could apply to your child:

- becoming either over-excited and using these behaviours to calm down or feeling bored and trying to create some excitement

- feeling anxious, angry, upset or distressed because of sensory or emotional overload, and expressing these emotions through these behaviours or using these behaviours to soothe themselves

- being in pain because of some physical problem such as a toothache or ear infection

- and finally, the behaviour may have started for any of the above reasons but then became a habit for the child even though the original reason no longer exists.

How can you reduce these behaviours?

Such behaviours cannot be removed entirely. However, they change with time. And using the tips below, you can make them less disruptive and more acceptable for the child and others.

First, consider whether there may be a physical cause that needs to be treated.

Next, make observations, as you have learnt to do earlier and reduce the conditions or situations that may trigger, maintain, or worsen your child’s behaviour.

Practical tips worth trying:

- Regular daily vigorous exercises often reduce such behaviours

- Do not let these behaviours put you off from doing joint fun activities with your child, rather do more of them if possible, without worrying about trying to stop stimming.

- Instead of showing negative emotions towards stimming, show positive and engaging emotions towards your child and keep building your relationship with the child.

- Whenever your child does such repetitive behaviour, start an activity of your child’s choice, which has been practised earlier. Praise and reward your child on starting that activity.

- For stimming, which may be socially inappropriate use pictures or words (depending on the child’s understanding) to convey to your child that he/she can do stimming in his/her room or later. That will improve your child’s self-control.

- Regularly praise and reward your child for not stimming. Do not shout at the child or use physical punishment for doing these behaviours.